attributes essential for field army command: professional competence, courage (physical and moral), initiative, self-confidence, and intuition, the ability to see and feel things in the context of time and space

We thank all those who contributed entries to our latest Whiteboard where we asked the following question:

State, with no explanation, who you think is the greatest American field army (or army group) commander, then make the case for who is the second greatest American field army (or army group) commander.

This proved to be a challenging exercise for our respondents, and several commented on the difficulties of choosing from among the many great generals in U.S. history. Military historian Len Fullenkamp well summarized the difficulties, “To compare army command over a span of 200+ years asks one to compare the complexities of span of control, ability to see the battlefield, logistics, questions of policy and strategy, etc, not to mention, the capabilities of the enemy forces.” He also argued that commanders from the Cold War to present were mere “large cogs in much larger machines,” which constrained their abilities to act and thereby “achieve recognition for some measure of autonomous action deemed worthy of praise.”

Nonetheless, the following five entries were chosen by our editorial staff as the best submissions. Several highlight commanders whose accomplishments were indeed great but overlooked nowadays:

1. MATTHEW MCGREW, LIEUTENANT COLONEL, U.S. ARMY

(1st) Ulysses S. Grant; (2nd) Anthony Wayne

In the pantheon of America’s great field army commanders, General Grant is clearly first among equals. In the crowded field for second are several names familiar to most students of American history such as George Washington, Winfield Scott, William Sherman, and Matthew Ridgway. This author humbly proposes that while they were all able commanders the distinction of second greatest goes to Major General Anthony Wayne. With a force of less than 3,500 soldiers, he defeated a much larger Indian force supported by the British and forced the withdrawal of British forces from their illegal forts in the U.S.

MG Wayne was not a career soldier. He joined the military at the outset of the Revolutionary War serving with distinction from 1775 until 1783, before leaving active service. President Washington recalled MG Wayne to active duty in 1792, in spite of personal misgivings, to command US Army forces in the Northwest Indian War after the disastrous defeat of MG St. Clair by the Indian confederation in 1791.

This ended up being an astute decision. In the course of the next three years, MG Wayne reorganized his forces, training them in new tactics, all while continuing to fight a defensive battle against raiding Indian forces supported by the British. He reorganized his force of 3,000+ soldiers into 4 sub-legions, self-contained units with 2 battalions of infantry, a rifle battalion (light infantry skirmishers), a troop of dragoons, and a battery of artillery. This precursor to the modern BCT allowed American forces to advance separately into the Ohio valley and pursue Indian forces.

While his force is small compared with modern field armies, MG Wayne’s force consisted of 2/3 of all existing regular army forces combined with frontier militia forces. Using this force, he waged a successful campaign that achieved significant objectives on behalf of the United States government. His actions opened up 100,000 square miles of territory to settlement and finally forced the British to conform to the territorial agreements in the 1783 Treaty of Paris.

2. ANTHONY PEEBLER, STUDENT, TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY

(1st) George Washington; (2nd) Nathanael Greene

The U.S. military has no shortage of great generals throughout its history. Field Commanders such as Ulysses S. Grant and George Patton accomplished great feats, but with more resources and more powerful armies than the enemy. America’s first conflict was very different however, and its greatest field commander George Washington and second greatest Nathanael Greene both excelled at winning while outnumbered.

In 1780, Greene inherited a dire situation, taking command of what little remained of the Continental Army in the South after its humiliation at Camden earlier in the year. British General Cornwallis planned to advance through the south towards Virginia. Camden proved that the Americans could not face the British on even terms, so Greene divided his forces and started a long strategic retreat through the Carolinas towards Virginia. Cornwallis was forced to divide his forces as well and pursue Greene far from British coastal bases of supply, allowing the Americans to find more favorable fighting conditions. One of Greene’s forces under Daniel Morgan scored a significant victory at Cowpens, fielding superior local numbers.

Cornwallis pursued Greene’s forces north, engaging in costly skirmishes that were British victories, but gained no strategic advantage. At Guilford Courthouse Greene finally turned and faced Cornwallis in a major battle. Cornwallis won, but was forced to return to the coast to replenish his forces, eventually moving along the coast towards Virginia. Greene, against all odds prevented a superior British force from controlling the south.

Greene reversed an impossible situation and was able to weaken his enemy enough to prevent them from accomplishing their objective. He understood the importance of a larger objective over tactical victories while keeping his army one step ahead of the enemy. He falls short of Washington only because Washington employed this strategy over a period of several years.

3. GEORGE SCHWARTZ, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR, IMMACULATA UNIVERSITY

(1st) George Washington; (2nd) George H. Thomas

In the aftermath of their respective wars, history was not as kind to General George H. Thomas, the second-best field army commander in United States military history, as it was to General George Washington, our greatest. While Washington has been lionized for his leadership and strategic savvy, his operational record was actually mixed; Thomas, however, never lost a battle during the Civil War.

His record of success began when he was a division commander in January 1862 at the Battle of Mill Springs, one of the first major Union victories of the war. Thomas would go on that year to have roles in the Union victories at Shiloh, Corinth, and Perryville.

In 1863, he would repeatedly draw victory from the jaws of defeat. Although hard-pressed, he held the center at Stones River. He earned the moniker, “The Rock at Chickamauga,” after rallying the remaining Union forces to make a stand with him when all appeared lost and the army commander fled. Assuming command of the Army of Cumberland while it was surrounded in Chattanooga, his troops stormed the steep slopes to take the Confederate positions on Missionary Ridge.

Throughout his career, Thomas had held a variety of positions that had allowed him to master important functions, including planning, logistics, and training. He utilized all these skills at Nashville in December 1864 to cobble together disparate forces and lead them to destroy the army of General John Bell Hood in just two days.

It was textbook Thomas—methodical preparation and a decisive strike when the conditions were right—but some of his contemporaries, including his superior, U.S. Grant, would cast Thomas as slow and thus his historical legacy was sealed. In a field replete with masters of field armies, Thomas has always been underrated, but his record demonstrates his mastery.

America’s first conflict was very different, and its greatest field commander[s] excelled at winning while outnumbered

4. LEN FULLENKAMP, MILITARY HISTORIAN & FORMER PROFESSOR, U.S. ARMY WAR COLLEGE

(1st) ULYSSES S. GRANT; (2nd) GEORGE S. PATTON

Asked to name the 2nd best U.S. field army commander since the inception of the U.S. Army one has a short list from which to consider candidates. Since the American Revolution through the wars in Korea and Vietnam fewer than a hundred men have held such a command. Here I am distinguishing field armies that were fighting armies as opposed to field armies that functioned as administrative organizations. Examining that list, and including Confederate officers from the Civil War, Ulysses S. Grant rises to the top as the best of the lot.

For sentimental reasons I lean toward naming George Washington as the best to have commanded a field army, but as he was both the Continental Army Commander and that army as a fighting force he is to be considered a supernumerary. Field (fighting) armies under Grant’s personal command were victorious at Ft. Donelson, fought and maneuvered against Confederate forces at Shiloh, and persisted and prevailed in the Vicksburg Campaign. Subsequently Grant ascended to command of what later came to be called Army Groups, a different a more complex level of command. As an aside, Grant heads that short list of talent even when compared with those who held similar commands in WWII. Grant’s style of command reflected a balance of control and direction with empowerment of subordinates to achieve his objectives.

Second to Grant is George S. Patton. Although William T. Sherman or Philip Sheridan are competitive for the second place, Patton secures that position on the merits of his growth over time as a combatant commander. The Patton who commanded the 7th Army in Sicily matured and became more effective as commander of 3rd Army from Normandy through the end of the war. Sherman was a far better logistician than Patton and Sheridan has the edge when it comes to the ruthless application of cavalry forces in pursuit operations, but Patton comes out on top when one considers the nature of war during WWII. Grant, Patton, and the others mentioned possessed the attributes essential for field army command: professional competence, courage (physical and moral), initiative, self-confidence, and intuition, the ability to see and feel things in the context of time and space.

5. DOUGLAS DOUDS, PROFESSOR OF OPERATIONAL ART & THEATER STRATEGY, U.S. ARMY WAR COLLEGE

(1st) ULYSSES S. GRANT; (2nd) GEORGE G. MEADE

MG George Gordon Meade, Army of the Potomac commander from 1863-1865, is the second best field army commander. Foremost, he deserves this title because no one ever considers him first! Even though he led a winless army (Antietam = tie) to a decisive victory in the largest and most bloody battle of our nation’s most bloody war, Meade is an afterthought to even his Gettysburg antagonist, Robert E. Lee. Moreover, that Meade accepted command only three days before his Gettysburg victory is testament to his technical, conceptual, and heretofore, novel interpersonal skills with ranking subordinates and Washington.

Meade was eminently qualified to command. A West Point artilleryman, he became an engineer. He was a Mexican War staff officer and the Civil War brought infantry brigade, division, and corps commands. Besides logistician or cavalryman, Meade served in every branch. Technically, few better understood an army’s elements’ roles and functions. Testament to his acumen, a quick to relieve Lincoln made Meade the war’s longest serving Union field army commander.

However, command is more than technical excellence, Meade succeeded because his fellow commanders trusted him.

Ultimately, Meade created harmony in an army that had not won. Changing the trajectory of an organization is often considered the hardest of leadership tasks and this fact alone eliminates Civil War aspirants like Sherman, Thomas, and Sheridan who inherited victors and fought Confederate eastern theater rejects. Meade took over amid a campaign for the nation’s survival, fought the Confederacy’s best … and won … and sustained that winning culture until the war’s end.

If some flaw is required to prove the humanity of a great commander or a colorful nickname, Meade’s volcanic temper and spectacled bearing earned him the nom de guerre “old goggle-eyed snapping turtle.” Again, Meade rises, but not to first. That distinction belongs to U.S. Grant.

The views expressed in this Whiteboard are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

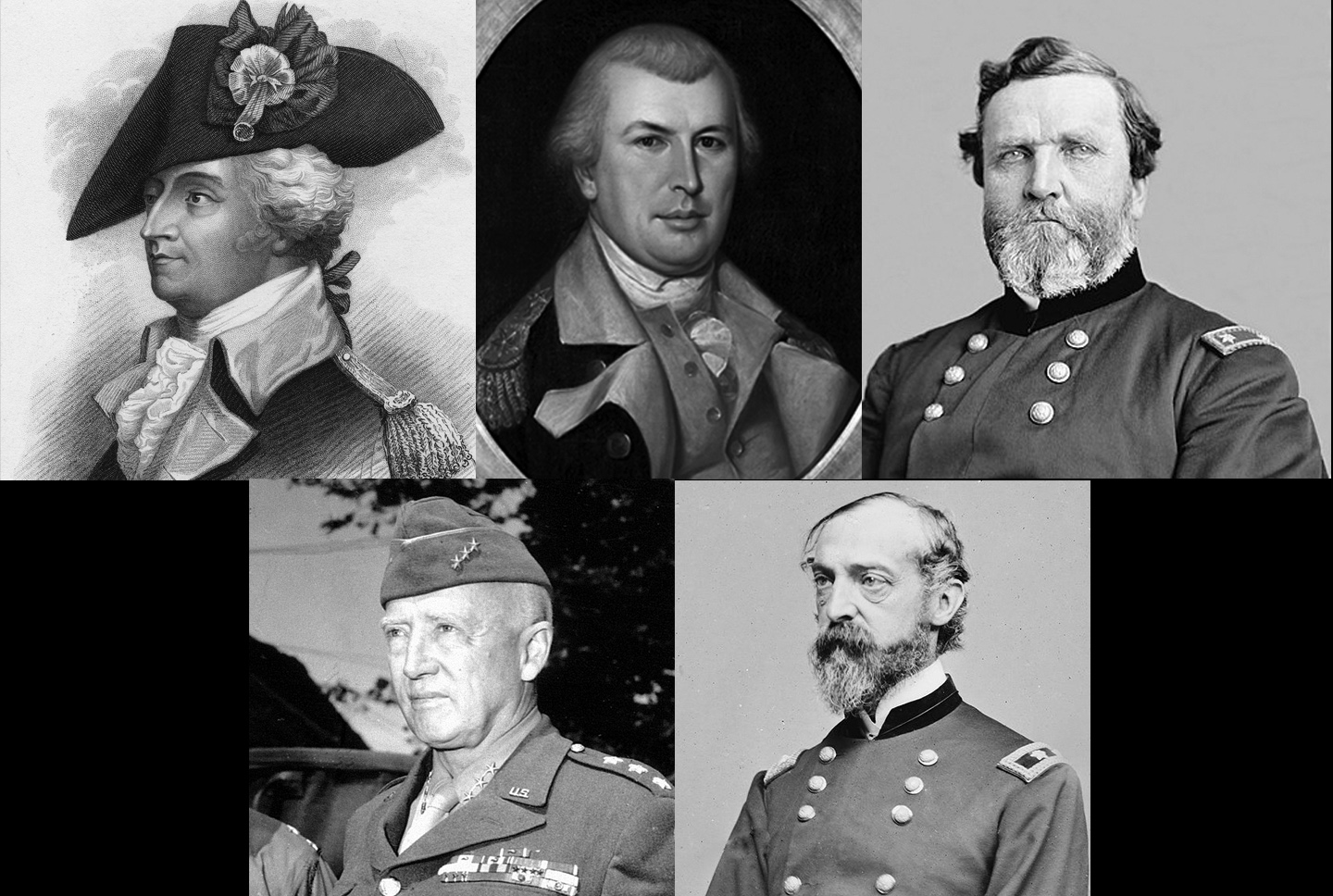

Image: Top Row (L to R): Anthony Wayne (by Trumbull and Forest, 18th c.), Nathaneal Green (by Charles Wilson Peale, 1873), George H. Thomas (by Matthew Brady, bet. 1855-1865), George S. Patton (U.S. Army Photo), George G. Meade (by Matthew Brady, bet. 1855-1865). All images courtesy Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Image composed by Tom Galvin

Other Releases in the Whiteboard series:

- THE ADMINISTRATION’S TOP FOREIGN POLICY PRIORITY (A WHITEBOARD)

- AFTER 2020, WHAT’S NEXT? (A WHITEBOARD)

- IMAGINING OVERMATCH: CRITICAL DOMAINS IN THE NEXT WAR (A WHITEBOARD)

- THAT ONE MOST IMPORTANT THING: (A WHITEBOARD)

- SHALL WE PLAY A GAME?

(WARGAMING ROOM) - WAR(GAMING) WHAT IS IT GOOD FOR? (A WHITEBOARD)

- LEADERSHIP ROLE MODELS IN FICTION REVISITED: (A WHITEBOARD)

- WHAT GOOD IS GRAND STRATEGY? (A WHITEBOARD)

- THE UNITED NATIONS’ GREATEST ACCOMPLISHMENT: (A WHITEBOARD)

- LEADERSHIP ROLE MODELS IN FICTION: (A WHITEBOARD)